On November 26, 326 Constantine announced the transformation of Byzantium in the new capital of the Roman Empire, named after him Constantinople. All aspects of the new city which were reminiscent of Rome were emphasized. Constantinople had seven hills like Rome and the narrow sound (the Golden Horn) which provided a natural port was compared to the Tiber and Constantine built a quarter on a hill on the other side of the Golden Horn in imitation of Trastevere. This quarter was called Sykae and again following the pattern of what had happened in Trastevere (Ripa Romea) it became the preferred settlement of foreigners. The quarter became known as Galata, after a prince from Galatia who settled there. The Venetians settled in Galata, but, as a result of the support given by Venice to the Byzantine Emperor in his fight against the Normans, they moved to Constantinople and Galata became the residence of Genoese merchants.

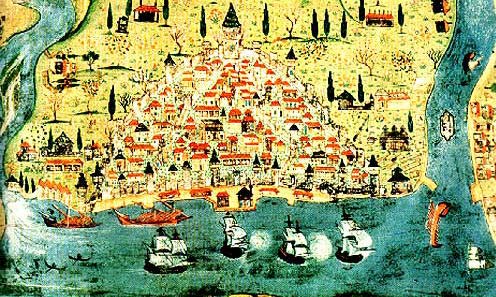

XVth century Ottoman Map of Galata

Both Genoa and Venice profited by the frequent dynastic quarrels among the members of the Byzantine imperial family to increase their influence and obtain trade rights. They also secured for their merchants a sort of capitulation rights, by which the merchants could form colonies, under the direct jurisdiction of their consular representatives. Galata therefore evolved into a type of independent city-state, similar to those existing in Italy. Because the Genoese central government was rather weak, Galata rulers often took sides in the continuous fights among Byzantines, Serbs, Ottomans, Bulgarians, which responded to their immediate advantage, rather than to the policies of their distant motherland. They strengthened the defenses of Galata by building a very high tower on the top of the hill (it is clearly visible in the map above).

In 1453 Sultan Mehmet II Fatih (the Victorious) laid siege to Constantinople. While a Genoese leader of soldiers of fortune, Giovanni Giustiniani Longo, responded to the appeals for help of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI, and with his 700 soldiers was able to effectively organize the defense of the city, the Genoese of Galata proclaimed their neutrality and as a matter of fact helped the Ottomans, by leaking information and by allowing them to move their fleet by land from the Bosphorus to the Golden Horn through a sort of railway built on the hill of Galata next to the walls of the town. As a result of this policy, Mehmet II, after having conquered Constantinople, renewed to the Genoese of Galata their trading rights. He required however the tower to be lowered and the walls to be broken in several places.

View of the Golden Horn, Constantinople and the Marmara Sea from the Galata Tower

| ||

Both Genoa and Venice profited by the frequent dynastic quarrels among the members of the Byzantine imperial family to increase their influence and obtain trade rights. They also secured for their merchants a sort of capitulation rights, by which the merchants could form colonies, under the direct jurisdiction of their consular representatives. Galata therefore evolved into a type of independent city-state, similar to those existing in Italy. Because the Genoese central government was rather weak, Galata rulers often took sides in the continuous fights among Byzantines, Serbs, Ottomans, Bulgarians, which responded to their immediate advantage, rather than to the policies of their distant motherland. They strengthened the defenses of Galata by building a very high tower on the top of the hill (it is clearly visible in the map above).

In 1453 Sultan Mehmet II Fatih (the Victorious) laid siege to Constantinople. While a Genoese leader of soldiers of fortune, Giovanni Giustiniani Longo, responded to the appeals for help of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI, and with his 700 soldiers was able to effectively organize the defense of the city, the Genoese of Galata proclaimed their neutrality and as a matter of fact helped the Ottomans, by leaking information and by allowing them to move their fleet by land from the Bosphorus to the Golden Horn through a sort of railway built on the hill of Galata next to the walls of the town. As a result of this policy, Mehmet II, after having conquered Constantinople, renewed to the Genoese of Galata their trading rights. He required however the tower to be lowered and the walls to be broken in several places.

| ||

The reason why the Genoese built such a high tower can be easily understood, by going up to its terrace. The tower allowed the view of the open sea beyond the hills and the buildings of Constantinople, so that the Genoese could early detect the arrival of their own ships or of hostile fleets.

| ||

But the hopes of the Genoese to continue their profitable trade in the Black Sea after the conquest of Constantinople by Mehmet II, were short-lived. Memet II had a clear vision of his target of effectively unifying his possessions in Asia and in Europe and prior to attacking Constantinople he built a fortress on the European side of the Bosphorus which controlled the traffic in the strait. It is known as Rumeli Hisari the fortress of Europe, as Europe was called by the Arabs and the other Muslim nations with names derived after Rome. The Ottoman cannon were able to stop any ship trying to travel without permission.

| ||

The Genoese influence in Galata gradually diminished, especially when in the XVIth century the Genoese fleet, led by the Admiral Andrea Doria, supported the Emperor Charles V in his fight against the Ottoman bases in northern Africa (capture of Tunis, 1535). Francis I, King of France sided with the Ottoman and his policy was in general followed by all the French rulers. This alliance led to France becoming the nation protecting the Catholic merchants living in the Ottoman Empire and there are signs of this influence in some coats of arms which can still be found in Galata. The French poet Andrea Chenier was born in Galata. In the little (and hidden) church of St. Peter and Paul's burial incriptions show that a certain number of Genoese families continued to live in Galata until the XIXth century. In the XIXth century Galata and the area behind it, known as Pera, underwent a great expansion: banks, shipping companies, theatres, shops gave to the Ville de Péra a very Belle Epoque appearance, and only a few old buildings of Galata were spared.

No comments:

Post a Comment